This article is a compilation written by Nyalra at the end of 2023, when he underwent nasal surgery in an attempt to regain his sense of smell.

------

I’d been going to a big hospital in Tokyo, hoping to regain my sense of smell, but once again, no luck.

I’ve followed the chain of referrals: local ENT → big Tokyo hospital ENT → the “strong” doctor at the big Tokyo hospital ENT → the plastic surgery department at the same hospital.

And still, nothing worked.

Now I’ve been handed yet another referral, this time to another major Tokyo hospital with an especially strong ENT department. That’s where I’ll head next.

I’ve written here and there about my lifelong condition before, but since it’s messy to piece together, and also so I can explain it more easily when asked, I’ll summarize everything now.

First of all, I was born without a sense of smell. Not because of some vague sensory issue, but for purely physical reasons:

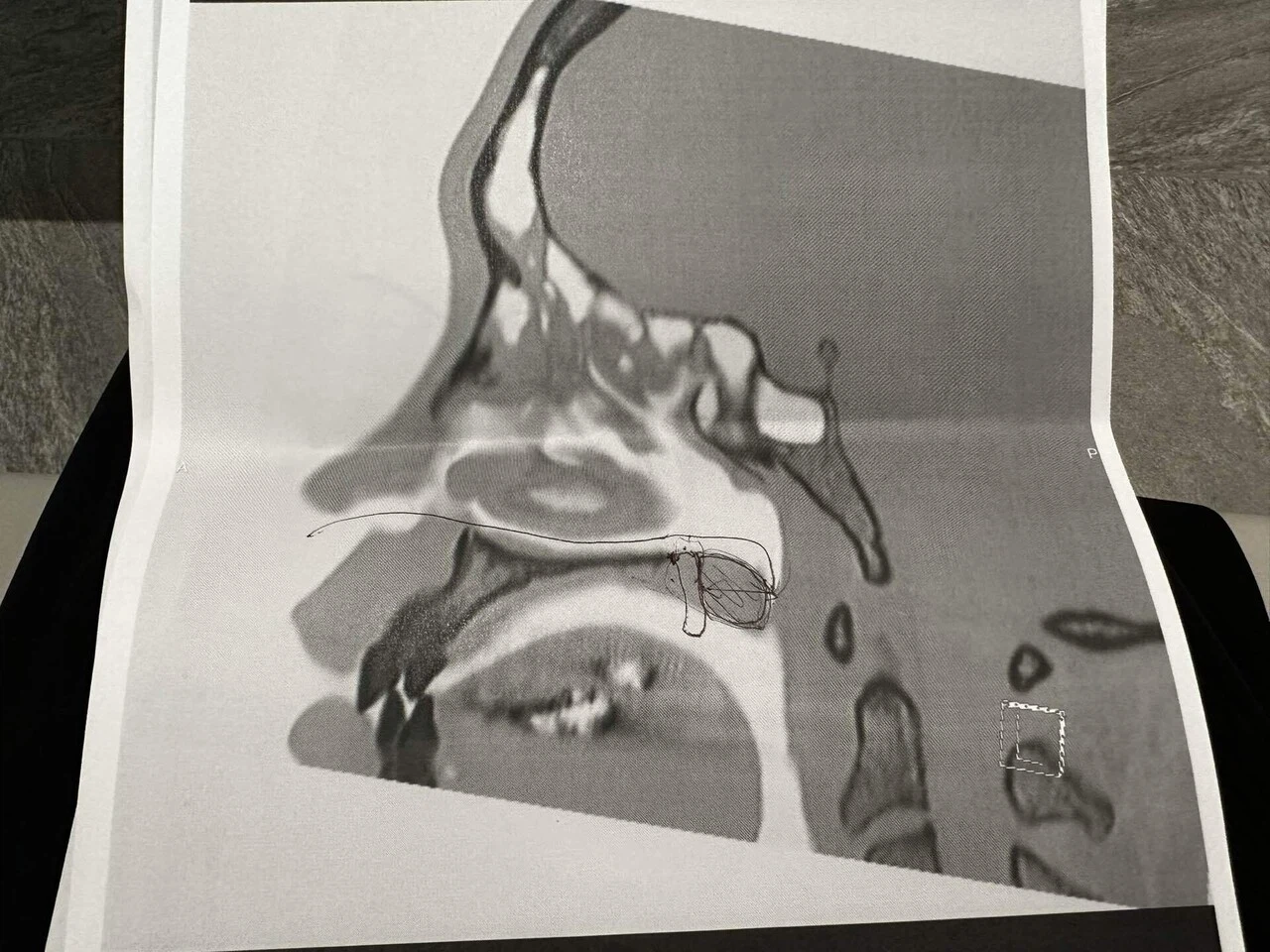

From birth, the bone deep inside my nose was abnormally narrow—practically sealed shut. Because of that, oxygen can’t pass through, which means I can’t breathe through my nose, and scents can’t reach me either.

With so little oxygen intake, I’ve been forced into mouth breathing, which in turn led to ruined oral health, poor eyesight (linked to the nasal passages), and insomnia from shallow breathing.

Until recently I didn’t even have health insurance (I’ll explain why later), but now that I finally do, I’ve managed to get dental exams and braces, and I had ICL surgery to fix my eyesight. Insomnia, though, still means I rely on sleeping pills. And the shallow breathing won’t ever be solved unless my nose itself is fixed.

As a kid, I was constantly in and out of hospitals, undergoing surgery every year—two months of hospitalization at a time. Doctors tried widening the bone at the back of my nose with tubes, or even cutting my uvula to approach from the inside of my mouth. But these procedures were high-risk for a child, and if they failed, the bone might be over-widened and I’d lose the ability to speak clearly. By third grade, the doctors and my mother decided to give up and wait until adulthood.

Of course, missing school for two months every year made it impossible to fit into the classroom. I became withdrawn. My mother, raising me alone, never scolded me for skipping—she just gave me books and games instead. For me, undiagnosed autistic at the time, being able to stay home and immerse myself was actually a blessing. I would’ve liked braces, but as a single-parent family we had no money for that. In the end, it was a small thing.

At 18, my mother remarried. I clashed completely with my stepfather (in hindsight, it was just teenage rebellion), and after dropping out of university I cut ties with them. I moved to Tokyo and started room-sharing with an online follower.

Since I was cut off from my family’s insurance, and out of pride I swore never to rely on them again, my health insurance lapsed without me realizing it. With no money and no insurance, the path to adult nasal surgery crumbled like a sandcastle.

Without insurance, I couldn’t even get proper prescriptions for sleeping pills. I started importing shady foreign drugs online and abusing them. It was a terrible period. But during that time I kept posting essays on blogs and note, and gradually I began to get work from it. Still, I couldn’t pace myself, and the pressure of human relationships overwhelmed me. I developed adjustment disorder and eventually needed treatment and medication for schizophrenia.

At that point, those around me—out of kindness—ran around to city offices and hospitals on my behalf. Thanks to them, I finally got health insurance again. After about seven years, I was able to go back to a hospital. I visited a psychiatrist, got a proper diagnosis and medication. It was then I officially learned I was on the autism spectrum. Not that it bothered me—I’d already known it in my bones.

At last, my mental state stabilized. I began focusing on creating what I wanted.

I planned and produced a game, and when it was finished, I earned a proper sum of money. With my producer co-signing as guarantor, I could finally afford surgery for my eyes, orthodontics for my teeth, and treatment for my nose. That was about a year ago.

Since then, I’ve been bounced from hospital to hospital. Records show I was at Ryukyu University Hospital as a child, but what department, what procedures, what diagnoses—I have no idea. Without those records (and without being able to contact my mother), doctors are hesitant.

My condition is rare, and if they mess up, my nasal bone could be over-widened, leaving me unable to speak properly. No ENT or plastic surgeon wants to take that risk.

So even this time—when I thought the big hospital in Shinjuku might finally work out—it didn’t. Now I’ve been referred onward to a hospital in Shimbashi. The journey continues.

If I ever do gain a sense of smell, I’d love to experience scents and flavors like a normal person. But that day still seems far away.

Trying to keep things positive, I once tweeted: “If it’s me, I could hug even a sweaty otaku who hasn’t bathed.” Two male otaku saw it, and at Comiket they actually asked for hugs. So I sighed, and hugged them. It was summer Comiket, so the smell must have been awful—but for me, it didn’t matter. The two of them went home looking happy.

If that made someone’s day, then maybe, for now, that’s good enough.

-----

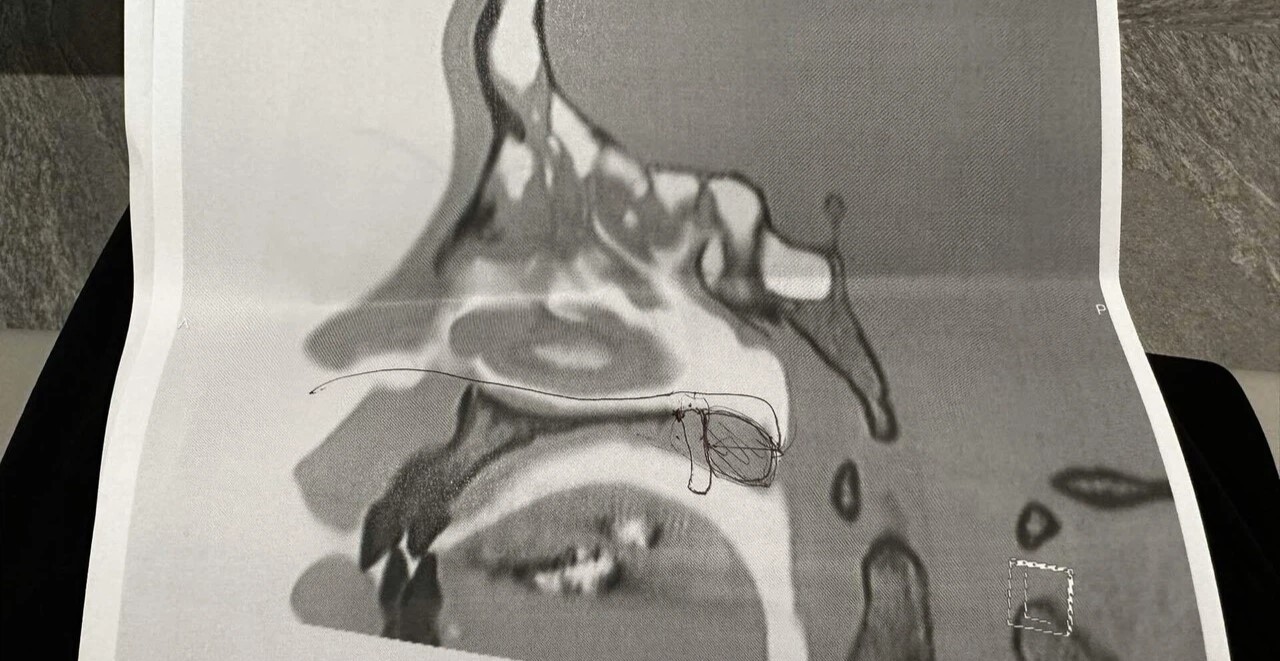

※ Following the tests at the major hospital, my condition was provisionally labeled as “congenital choanal atresia.”

In other words: I was born with the back of my nasal passage blocked, so I can’t breathe through my nose—and along with that, I have no sense of smell.

It has been decided that the surgery will be performed at that hospital.

Surgery and Blood

As scheduled, I underwent nasal surgery.

To state the outcome first: it’s still unclear whether I’ve regained my sense of smell.

But at the very least, the surgery to open a large passage between my nose and mouth was a success.

To the doctors—thank you so much. Truly.

Just as promised, the specialist and the hospital I was referred to were top-notch.

The only drawback was that from my bed, writhing in agony, I could see people laughing and enjoying themselves up in the Tokyo Tower observation deck right outside the window. Aside from that, it was perfect.

My condition stems from the fact that, for some reason, I was born without a connection between my nose and mouth. Which means air could never pass through my nose.

Normally there’s a passage that connects the two. What this surgery did was force that passage open. Even in words it sounds painful. In reality—post-op—it hurts so much I want to die. It really hurts that badly.

They inserted instruments through my nasal cavity, but since that wasn’t enough, they had to insert more through my throat as well. That’s why respiratory surgeries are said to be so complex: the anatomy is difficult to reach. They cut open the back of my throat, the ceiling of my mouth, and stitched it afterward. The pain is unbelievable, and every time I speak I spit up blood. For now I can hardly speak at all. Writing these words is the only way I can communicate.

Still, thanks to the skill of the surgeon, the passage was successfully opened.

They cut through the hardened tissue in the depths of my nose—toughened from years of failed childhood surgeries—scraped together nasal mucosa to guard against it sealing shut again, and inserted tubes for several days.

After waking up, both my nose and mouth were drenched in blood around the clock. Splitting through that much flesh and bone inevitably ravages the body. This time they drove a hole two fingers wide through the flesh that had been sealed off. Every swallow feels like glass scraping down my throat, so I let saliva pool and then spit it into the sink. It’s always mixed with blood. The shower stall turns red in minutes.

The first day passed in nothing but pain and blood management.

For now, all I can do is remain still, letting the new passage stabilize. My nasal cavity is clogged with massive bleeding. At this point I have neither the ability nor the margin to perceive “smell.” Not with tubes jammed in.

The general anesthesia, though—it was as pleasant as ever. A mask and an IV drip send the anesthetic coursing in, and before I know it, I’m forced into sleep. If possible, I’d like to stay that way forever. There’s a small delight in that simulated death, being dragged into unconsciousness.

The anesthesiologist, a kind woman, held my hand and joked, “It’s only an old lady’s hand you’re holding, you know.” But to me, it meant everything. I told her, “It’s warm,” as my consciousness faded. That may have been the last thing I said all day—maybe for several days.

In the haze, somehow the hand I was holding turned into Misono Mika’s (probably because I’d just seen her on my timeline).

If Mika was holding my hand, then surely it was fine. At the same time, I thought, “Sorry—I don’t even play Blue Archive…” I only knew her from illustrations. Suddenly I was forcing an unrelated otaku girl to hold my hand. But her expression of compassion was so radiant it erased every trace of surgical fear.

Just before surgery, those are the kinds of thoughts that fill the mind.

And I suspect death will be the same. No matter what kind of life you’ve lived—

if, right before you die, you glimpse a hallucination of a beloved character, wouldn’t that be happiness? That’s enough.

I woke to agony. The pain itself was proof of the surgery’s success.

My throat was stitched shut, so no words would come. Yet the surgeon praised my effort and explained the next steps. I couldn’t even say “thank you.” My lower body was strapped down, my movements restricted. But above all I wanted to convey my gratitude. My mind overflowed with it—so much that the adrenaline even dulled the pain.

A nod might be mistaken for mere assent. I had no strength for writing notes. So, half-unconsciously, I closed my eyes, pressed my palms together, and bowed deeply. The gesture of prayer.

I prayed—for the first time in my life—for another human being.

That the doctor who became my savior might be blessed with great fortune.

Post-op Day 1: Intense Pain

I knew, of course, that the anesthesia only works during surgery, and that the real pain would hit afterward. Still, the reality was far worse than I imagined. I didn’t even have the energy to write a long entry, so my diary update is late. Right now, with painkillers, I’m relatively stable. I’m okay.

Since they cut open both my nose and palate, the swelling is massive. The bleeding from nose and mouth hasn’t stopped, and every spurt comes with pain. Eating and speaking are impossible, which is exhausting in itself. On top of that, my body is worn down and running a slight fever of around 38°C. It’s a full combo of damage to my body—pure hell.

Even so, I can still get online in between. When the painkillers are working, doing ordinary things helps keep me grounded. I scroll Jump+ like usual, exchange small messages with friends. In reality I can’t speak, but online I can communicate in text. That’s such a relief.

Right now, a long tube runs from my nose down into my throat. That’s what keeps the newly opened passage from closing up. Obviously it hurts. You can probably imagine the pain of having a tube forced from nose to throat 24/7. That’s the pain I’m in.

And to make it worse, the tube slipped out and had to be reinserted. The first time, they put it in while I was under general anesthesia, so when I woke it was already there—I never experienced the “insertion.”

But this time, the blood loosened it, and it slowly slid out. They had no choice but to shove it back in—without anesthesia. Just raw force, driving it through from nose to throat. I was strapped to a chair while the doctor rammed it in. My throat was too swollen to scream, so in the end I probably looked ridiculously stoic. Honestly, it ranks among the top five most painful experiences of my life. After that, they taped it down carefully so it wouldn’t slip again.

And so, my first day after surgery ended as a battle against pain. I expected as much, so it’s fine. I won’t be able to test my sense of smell until the packing is removed from deep inside my nose anyway. Not that I’m in any shape to care.

Enough about the suffering—let me write about the benefits.

The obvious one: with the tube in place, air now flows from my nose into my throat. In other words, I can breathe through my nose! For the first time in my life, I can actually close my mouth for a long stretch. I can’t manage it for long yet, but even so, breathing feels unbelievably easier.

And here’s another surprise: breathing through the nose means my mouth and throat don’t dry out. Up until now, I was always mouth-breathing, so my mouth would dry instantly, forcing me to constantly sip water or tea. If you’ve met me, you probably remember—I always had a drink in hand. That was why.

But now? Even if only for two minutes at a time, I can keep my mouth closed, and my mouth stays moist. It’s comfortable in a way I’ve never known. I don’t wake up constantly at night, parched and reaching for water. For now the pain eclipses everything else, but if this lasts, many of my complaints might finally ease. That makes me happy.

Of course, once the tube comes out, there’s a high chance the tissue will close again and I’ll lose this ability. I may have tasted a moment of “normal nasal breathing,” only to return to mouth-breathing. This surgery used up the remaining nasal mucosa, so there won’t be another attempt. The likelihood of closure is very high.

To experience “ordinary life” just once, and then be thrust back into disability—

In some ways, that’s the cruelest fate of all. That’s sad, even for me. But there’s nothing I can do. Maybe the hole will stay open, even slightly, and that alone will be better than before. Best not to dwell on the inevitable.

For now, I have no choice but to live with the pain. Still, I’ve always felt that pain which benefits me—whether from surgery or from training at the gym—feels almost like a kind of ascetic practice. This extraordinary suffering will make me value ordinary life all the more when I return to it. It’s in moments like this, fighting pain, that one truly understands how blessed normal days really are.

That is the moment when one learns the meaning of enough.

Post-op Day 2: Probably the Peak of Pain

I’d assumed the peak of the pain would come the day after surgery, but today was worse.

From the cut and swelling in my palate, agony radiates to my eyes and ears. It feels like my head is being crushed in a vise—like some demon machine pressing down mercilessly.

On top of that, if I thrash around, blood spurts from nose and mouth, so I have to lie flat on my back, staring straight up. Even retching won’t come, since my mouth was cut open. And even after all this, there’s still the thought that if the nasal tube slips out, it might close up again immediately. It’s enough to break my spirit—but whether I break or endure, the reality is the same: all I can do is lie flat on my back. Reality is indifferent.

The worst part is swallowing. Every time something passes my throat, the pain is like glass scraping its way down. I even need courage just to swallow saliva. More often, I spit it into the sink. Drinking water or eating is practically suicidal. I gave up on meals and switched to IV nutrition. Fever and hunger attack me too, but when you’re already in a parade of pain, adding one or two more doesn’t change much.

Why do I have to endure all this torment? Simply because I happened to be born with a defective airway. Every human is born with strengths and weaknesses. Mine just happened to be in the respiratory system. It’s only probability. I drew a bad lot, that’s all. Thinking in terms of blame—whether self-blame or blaming others—would only wreck my spirit further. I’m quietly grateful that I’ve been able to draw that line these past few days.

The swelling seems to have gone down a little; I can manage a few words. Today, a nurse washed my hair for the first time in ages. She apologized, “Sorry, I’m not as good as a hairdresser,” and I slowly replied, “A…ri…ga…to.” I would have liked to say “Thank you very much” properly, but ten syllables are too many for me now. Through trial and error, I found that saying “Tasukarimasu”(appreciate it) works best. Six syllables I can manage.

Still, the inability to communicate is crushing. Wanting to say something but failing, being unable to “have a conversation”—it’s terribly sad. Writing this diary, knowing someone might read it, is a kind of salvation. Not that anyone’s scheduled to visit me, but even if they did, I couldn’t talk, and I’d only be showing them a bloody, wretched state. They’d keep their distance. For now, the brief moments when a nurse changes my IV or brings me painkillers—that fleeting exchange is what makes me happy.

The worse the suffering, the more blissful the drowsiness that comes once the painkillers kick in. Not only does the pain vanish, but drowsiness follows naturally. Pain fades, and with it, consciousness. When the IV painkiller went straight into my veins during the peak agony, the relief came so fast it felt incredible. Pain and release.

Maybe, if you abstract life enough, those are the only two phenomena that truly exist.

By the time I’m discharged, I’ll probably be wrapped in an overwhelming sense of liberation. The nasal tube will be gone, my mouth free, and for at least a while, I might be able to savor smell. For now, thanks to nasal breathing, my mouth stays moist—I no longer suffer the constant dryness. Instead, I struggle with timing when to swallow saliva (without painkillers it hurts), but even that is something to gradually learn, and it gives me small bits of joy.

Of course, I also think about losing it all again. After enduring such agony, only to taste nasal breathing for a moment and then have it taken away—that would be the cruelest thing. But when I finally accept that and am freed, the sense of liberation will be even greater. In that way, maybe this is a necessary ritual.

Post-op Day 3: Vitality

One thing that has always stuck with me is how Hitoshi Iwaaki, in the afterword to the final volume of Parasyte, closed by reflecting on the life force he felt in his own thumb as it healed after he accidentally cut it. Life itself is that mysterious, that captivating.

Now it’s the third day after my surgery.

As I’d sensed from last night’s unbearable pain—that was the peak. Things are finally turning toward recovery. My fever has dropped from nearly 39°C to the 37s, the nosebleeds that ran all day yesterday have eased, and the swelling in my cut throat is starting to go down enough that I can get a short sentence out. Though the tube remains stuck in one nostril.

It’s incredible: even after the inside of my head, the very center of my face, has been cut open and tampered with, my body is already regenerating in just a few days. That is undeniably the power of life. My whole body right now is demanding “life,” and learning to adopt nasal breathing as a new habit.

When it comes to nasal breathing, I’m still a baby. It’s only been three days since the function even became available to me. I don’t yet know the timing for swallowing, or how to sustain breathing only through my nose for more than a few minutes. But I can feel it, little by little—my breathing shifting from mouth to nose. I don’t wake with a dry throat anymore, because my mouth stays closed while I sleep. Oxygen flows smoothly into my lungs, and I don’t wake up in the middle of the night. What a convenient way to breathe.

…Okay, that last part’s a lie. Right now the fever and pain still wake me. But in time, that too will be a distant memory. As I learn the proper way to breathe, it will become natural. I’d rather not lose this calm bodily function now that I’ve finally found it.

And yet, it’s this very life force that torments me.

Because the root of my condition lies in the tissue sealing off the passage between my nose and throat. Each time surgeons cut it away when I was young, it would swell back even harder, solid as rock. That’s why my childhood was marked not by nasal breathing but by endless hospital stays. My earliest school memories are instead of lying in bed, battling through Wario Land 3: The Mysterious Music Box on my Game Boy Color, over and over. While everyone else was at their desks in school, I was alone in bed with Wario. It was actually pretty fun.

That meddlesome tissue inside my nose—once the thin green tube stabbing down my throat is removed—it will almost certainly grow back. The doctor said he’d tried using mucosa to build a wall, but I suspect life force will win. For some reason, my body “misunderstands,” thinking it has to close off the passage to survive, and so the tissue swells, tirelessly.

Just as the swelling in my palate and nasal cavity is already receding day by day, so too will it soon begin closing the passage once more. As I feel my own post-op recovery speeding along, I can already sense the nose tightening again.

Why?

Surely living with a nose and throat connected makes life easier. So why do my cells insist on blocking the airway, pushing me into unhealth? They are the very image of the “diligent fool.” Meaning well, they regenerate. Thinking they’re preserving my body, they toil on.

How could I hate them? They do it for me—or rather, more simply, for themselves. To live. Even if it ruins my ability to live normally, they don’t care. They’re life. There is no good or evil in it. Only a bug, when seen from the perspective of a “normal” body.

Right now, three times a week, I destroy my own body with training. I hoist unnecessary weights, strain and tear my muscles, then pour protein into the wreckage so they rebuild stronger. My chest has thickened, my abs are defined. That strength has surely helped me endure this surgery. In other words, I rely on vitality. I intentionally destroy and rebuild. I have my purpose, and life itself has its purpose. Sadly, in the depths of my nose, those purposes are in conflict. That happens.

Already, even here in the hospital, I’ve started working again. If I stay idle, I’ll be crushed after discharge. I’ll breathe life into the character of KAngel, and prepare to seed new stories and figures for the future. I begged the doctor, and my discharge day has been set for Thursday. Once the tube is out, I’ll just be “that guy who gets unusual nosebleeds.” If I can manage to speak one sentence at a time, I’ll get by. I can’t stay here relying forever on the kindness of others. And besides, the hospital bills are outrageous—each day costs too much!

So, whether or not I regain my sense of smell will be known only when they pull the tube on Thursday morning. Whether or not it closes again, no one can say. It’s all wrapped in mystery. Because that’s life.

Life force itself is what shapes the future. It’s not something a mere human can comprehend. My flesh lives on its own, and if it insists on surviving—even clumsily, even stupidly—then all I can do is carry it with me, as part of myself.

Post-op Day 4: Memories of July 1999

Day four after surgery.

Overall, I’m recovering. Still, a slight fever lingers, bleeding continues a little, and most of all, the pressure from the tube stuck in my left nostril has started sending sharp pain into my left ear. Especially when I swallow saliva—agony.

But that aside, things are fairly stable. The new trouble is that whenever I drink liquids, they immediately come out through my nose. Apparently, since my throat and nose are now connected, things flow backwards. I asked the doctor why ordinary people don’t constantly experience this too, and he explained: “Through countless experiences of eating and drinking, the throat muscles learn how to work, unconsciously preventing reflux.” Amazing—the human body. Everyone goes through that learning process as a baby. For me, this is all first-time. What do I do now?

So my current issues are only two: “ear pain from pressure” and “reflux during meals.” The first requires painkillers and patience, the second I can manage by tilting my head back when swallowing. Even with painkillers, I’m losing sleep from the ear pain, but compared to the peaks of day one and two, it’s bearable.

So hospital life today has nothing remarkable to note. If anything, it’s been nice to have free time to binge manga. I read Tetsuya Saruwatari’s new work Eihabu—an absolute masterpiece. The way his draftsmanship fuses with his sense of religion is overwhelming. Few artists can render violence with such divinity.

I’ll save detailed thoughts on good manga for after discharge. Since I’m still here in the hospital, let me share a memory from an earlier hospitalization.

As a child, I was often hospitalized for nasal surgeries. But one period is unforgettable. The time was the end of the century—July 1999. The very month Nostradamus had prophesied the “King of Terror” would descend and destroy the world. I was about five years old, alone in a hospital room.

In ’99, the occult boom was at its height. TV, magazines—everywhere horror, occult, doomsday theories. Even if you didn’t believe the world was ending, everyone felt some vague sense that “between ’99 and 2000, something big will change.” I even remember the fuss over the Y2K problem. But more than Y2K, it was my own dreams.

Hospital rooms are boring. Today, even a child could kill time with a smartphone, videos, games. Back then, entertainment meant the room’s CRT television, a Game Boy Color, maybe a few manga. So most of my hours were spent in front of the TV.

Naturally, in the midst of the boom, the TV stations weren’t going to not cover the “King of Terror, Angolmois.” Every channel ran programs hyping doomsday, aliens, you name it. They could say anything, no cost to them. As a child, I filtered information as best I could—but hearing it all, I half-believed that at the stroke of July ’99, a giant UFO would descend from space and disgorge the King of Terror to end the world.

If I’d been at home, surrounded by family and toys, maybe it would’ve been different. But there I was, alone in a hospital room at night. My mother went home after bedtime. Even without Nostradamus, a child left alone in a hospital feels anxious.

Add in the end of the world chatter everywhere, and it was unbearable. At 9 p.m., the lights went out in the room and hallway, leaving only the faint glow of the nurse’s station and the bathroom. I peeked out the curtains, but the bluish courtyard and mechanical lights of the opposite ward only deepened the horror-movie atmosphere. I quickly closed them again.

It was a long, long night. My memory is hazy, but for an hour or two I was convinced that if I fell asleep, the King of Terror’s UFO would crush the hospital. A five-year-old, trapped in a delirious panic.

What I wondered most was: “How seriously are the adults taking this?” The TV people were saying all kinds of things, but my mother had gone home unconcerned, and the nurses at their station worked as usual. So for ordinary adults, clearly it was “TV lies.” Just toxic airwaves. The truth was that nothing would happen, life would go on. …Or would it? In dramas, it’s always when the adults laugh things off that the catastrophe is real. My imagination ran in loops, simulating every possibility. Rationally, whether I slept or stayed awake had nothing to do with whether the cosmic king would come. But reason doesn’t help a child alone at night.

Eventually, I drifted to sleep. The next day my mother visited, the nurses carried on. Nothing happened. Nothing happened—but in that lay a strange disappointment. And the fact remains: in July 1999, I was a child alone in a hospital room, waiting for the end. I will never forget that night, and I will never experience that terror again.

Looking back, perhaps my obsession with horror and the occult ever since traces back to that single night of panic, irradiated by toxic signals. Maybe Angolmois came to my room alone. Maybe it still does. Even now, lying in a hospital at night, I remember that night.

Post-op Day 5: The Night Before Discharge, and My Voice

Day five after surgery.

Tomorrow morning, they’ll finally pull the tube out of my nose. From the day of the operation, nearly a full week has passed with a tube rammed from one nostril down into my throat, pressing against my face. Blood has streamed the whole time. The tube wedged up into my nasal cavity has even pressed against the spaces of my ear and eye, leaving me with congestion, conjunctivitis, and an ear infection. Maybe because of that, here on day five, I’m still burning with a fever over 38°C. Help!

But it’s just one more night to endure. At this point, whether I’m in the hospital or at home makes no difference. Once the tube is out and the packing removed, it’ll just be a matter of recuperating at home. Work is already piling up for after discharge, but well—I’ll just have to deal with it.

The swelling in my throat has mostly gone down, but with the tube in, I still can’t speak properly. At least the bleeding while talking has stopped. So maybe once the tube’s out, I’ll be able to speak fluently again. After a week of barely speaking at all, I’m not even sure if my voice will come out.

Yes—the voice.

Smell isn’t the only thing at stake here; the voice matters too. Since the very structure inside my nose has been altered, my voice should naturally change as well. Until now, with surgical swelling and the tube blocking me, I couldn’t really talk—but even so, from the little I’ve managed, I can tell my pitch has gotten higher. And, of course, it’s no longer nasal. Maybe it’s only a fleeting dream before everything closes up again.

Outside of puberty, when else in life does one’s voice change so drastically? It’s like I’m suddenly being recast with a different voice actor. That’s a joke, but still—when I do meetings over calls, will the other party even recognize it’s me? And how long will it take before I myself get used to it?

Until now, my condition meant my nasal passages were blocked at the bone level. I was the embodiment of a nasal voice. As a child I was teased, and even online it was sometimes mentioned. Since I only ever produced a nasal voice, I couldn’t even perceive the difference between “normal” and “nasal.” It was beyond a complex—I simply had no frame of reference.

Still, I knew from experience there were sounds I couldn’t pronounce right. For example, I can’t distinguish “na” from “ra” in my speech, even if in my head I’m outputting them correctly.

That’s why, among my already withdrawn school days, music class was pure hell. Being off-key and dragging everyone down meant I skipped class whenever I could. If I did attend school that day, I’d escape as soon as we had to move rooms for music. Luckily, from junior high it was elective with art, and in my technical high school there was no music at all.

Of course, I love listening to music. But singing or performing myself was never an option. Karaoke was out of the question. My most-played artists year after year are still Kraftwerk, YMO, and ZUN—and their associates. Always those three at the top. I’m more into instrumentals than vocals. Well, mostly techno, but I do listen to plenty of vocal tracks too.

Even so, when I released my own game, I felt I had to write lyrics for the theme song. After twists and turns, I ended up writing lyrics to four Aiobahn tracks. Two of them have been played tens of millions of times. Now I even get lyric requests for works unrelated to my own. One will be released sometime next year.

Never did I imagine my life would be this closely tied to music creation. Having never taken a single class, I still don’t understand pitch or scales at all. All I did was attach words to the wonderful instrumentals that came to me. Not self-taught—even less than that, untrained and clueless. My only tools were urgency and passion. The songs I wrote for KOTOKO, for instance, were pure fervor—no technique, no conscious skill. What I wrote were closer to poems.

Still, thanks to having friends’ songs reach so many people, my fear of music has eased a lot. For that, I owe Aiobahn. Honestly, I don’t know how he keeps sending me such wild, baffling instrumentals each time—but that’s his genius.

If my nasal voice is cured, maybe I’ll go to voice training and finally attend the music lessons I once ran away from.

In fact, I tried once before. I wanted to see if even with a nasal voice, my articulation could improve. The music school teacher was incredibly kind, heard my circumstances, and taught me the very basics. I asked, “How hard is it to understand me, really?” And the teacher said: “It’s not the nasal voice—it’s that you don’t look people in the eye when you talk.”

Right. Because I lacked confidence in my speech, my eyes wandered. Not even just in conversation—simply as a prominent autistic trait, I avoided eye contact. That made my voice sink into the ground. In other words, more than the nasal voice, it was my gloom itself that kept me mumbling.

That revelation blew my mind. I’d been missing the root of it all. That time I left after just the trial lesson, but once I’ve mastered nasal breathing tomorrow, I’d like to try again. I imagine a version of myself who can meet someone’s gaze and speak fluently…

Smell Test Results and Discharge

If life is nothing but a cycle of pain and release, then the moment of release finally arrived.

After a week with a tube speared from my nostril down into my throat—pressing on my eyes and ears, keeping me from speaking properly, even causing a high fever—they took it out.

That thing was long. No wonder my eyes were bloodshot, I got an ear infection, and my temperature stayed over 38°C. In normal life, nothing presses on the very center of your head like that. A week of loneliness with it lodged there. I endured. I really did. The rush of relief is so intense I almost forget why we did this in the first place; I want to jump around right now.

Before that, they also removed the gauze packed even deeper than the tube. That gauze protected the wound from pain, but it also sealed off the airway. So while air could reach my lungs through the nose, it didn’t travel upward—i.e., to the olfactory area. Now everything’s been taken out. I’m grateful.

First impression: pain.

It hurts so much. Every time air enters my nose it irritates the swollen tissue and lands like damage. I’m shocked at how full the world is of air. It hurts. It hurts, but it’s amazing. A brand-new sensation. Even if I sit there with my mouth closed and space out, air comes in through my nose and I can breathe. And pain aside, the ventilation itself actually feels good.

So everyone’s been living while feeling how pleasant “air” is? Or has it become so normal you no longer notice the liberation of wind passing through your nose?

In any case, my nose and throat are now connected. Honestly, it wouldn’t surprise me if it closes again by next month. But at this moment (swelling and pain aside), I’m normal.

For daily life, I still have to keep cotton balls in both nostrils. Because the surgeon used nasal mucosa as a wall to keep the forced-open passage from sealing shut, the inside of my nose is basically unprotected—everything turns into a wound. If I don’t keep it constantly moist, it’ll probably flare into something nasty. So for a while I’ll rinse with saline, then pack with cotton to humidify. In short, I still can’t use nasal breathing in everyday life. Ugh.

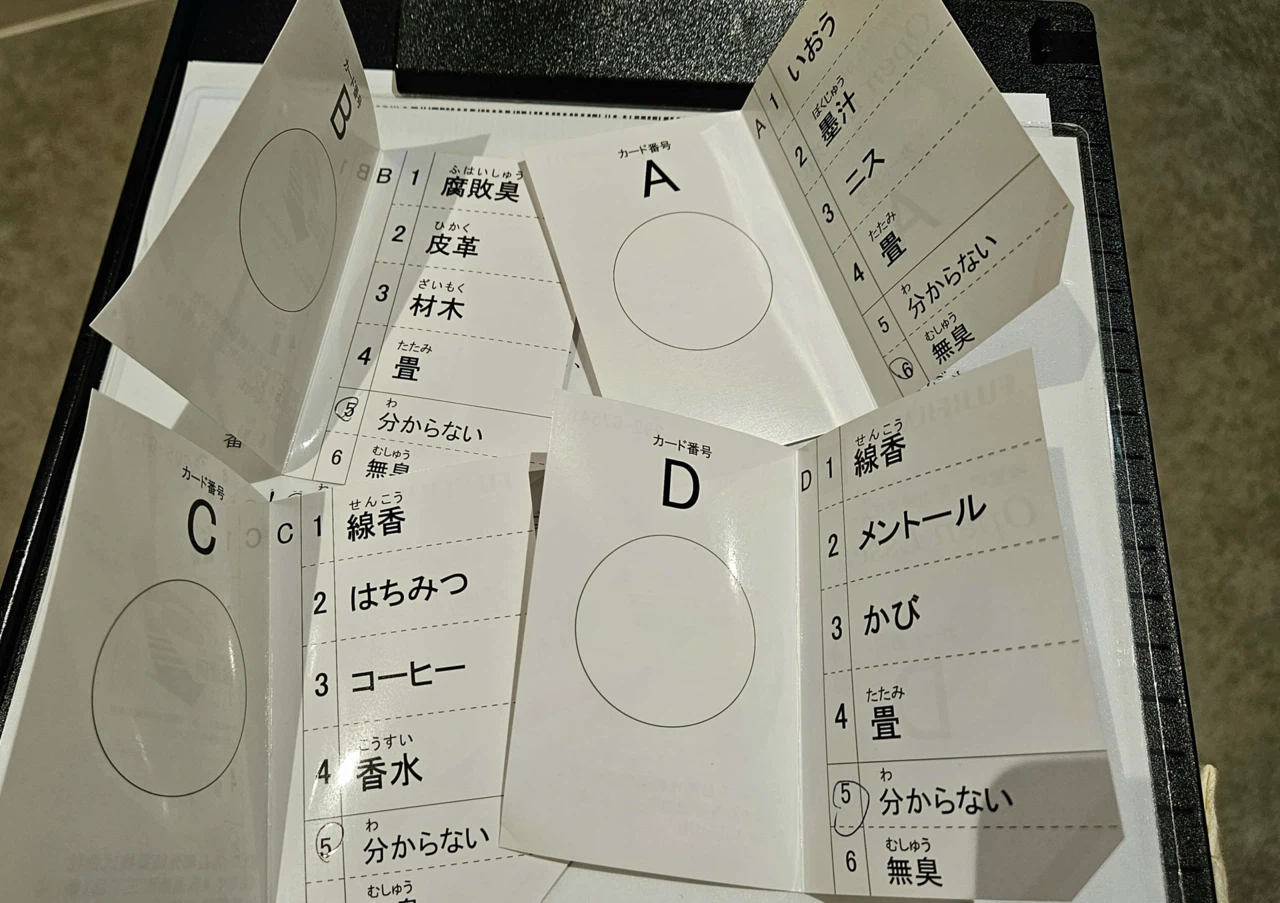

That said—time to test whether I can smell. The big hospital I’m at even has a dedicated olfactory testing room. They handed me a stack of scented papers and had me answer what each one smelled like.

I couldn’t tell…

I’ve never smelled anything before, so even if I felt something, I couldn’t infer “This is coffee!” or “This is tatami!” With no prior experience, there’s nothing to compare against; it’s all guesswork. But there wasn’t enough information to guess. We switched to trying some liquids that obviously should smell.

These must be what people call perfumes. As I brought each stick toward my nose, I felt a stimulus deep inside. It hurt—because I’m swollen—but a stimulus means recognition. This wasn’t odorless air; something was “attacking” my nose. After trying a bunch, I realized the stronger ones were actually hurting my nasal passages. Unpleasant. I answered, “So… I guess that means it stinks?”

Which is to say: several of the scented sticks—apparently things like peach or wood, “nice smells”—I labeled them all, without distinction, as “unpleasant,” “stinky.” “Stronger smell = stench.” With experience at zero, everything registers the same. Honestly, I expected this.

The doctor was thrilled. He even patted my shoulder and said, “You did it!” Seeing him happy made me happy. This is a big first step. Zero became one. And going from zero to one is far harder than going from one to a hundred. I’m just too much of a beginner to differentiate yet, but I clearly perceived “smell.” Even after 29 years of never using that sense, the nerves do fire. Beaming, the doctor said, “Discharge!” I was delighted. To be the person who let a great surgeon feel proud of their result—that fact made me happier than the sense of smell itself. I thanked him from the bottom of my heart and left the room.

And so: discharge. This is a matter of qualia.

What others call “sweet” or “pungent,” I, for now, perceive wholesale as “stinky.” But step by step, I’ll learn the differences. One day I’ll even grasp that there are kinds of “stinky,” and over a long time I’ll get to know what you otaku—yes, you—actually smell like.

Comments (2)

Leave a comment